Between the 50s and 60s, Rome became the capital of the “dolce vita”, a trend that involved actors and directors, as well as the bourgeoisie of the economic boom. It was a time where people surrendered to the fun and carefree climate of one of the most beautiful cities in the world. In Cinecittà, Italian and American films were shot because the production costs were lower than Hollywood and the city, Via Veneto in particular, was full of photographers and paparazzi, but also of writers such as Ennio Flaiano, who wrote the script for “La Dolce Vita” by Federico Fellini. In cafes and restaurants there were parties attended by the playboys of the time and the breakthrough stars.

While in the city there was a mundane climate, a cultural movement was born, personified by the new avantgarde of the Gruppo 63, with Nanni Balestrini and Umberto Eco. In the bars of Piazza del Popolo, intellectuals such as Alberto Moravia, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alberto Arbasino and Goffredo Parise used to meet, and didn’t mind attending the parties and the gatherings of the bourgeoisie and venues such as the Piper, were international artists would perform.

1960 was a year of change: the leftwing era started and in the USA the first catholic President was elected, J.F. Kennedy. In this scenario, Rome lived its “dolce vita”, with Fellini, Antonioni and Visconti. Yet, it was also a time of censorship and debate. The change involved also music, where the Beatlemania was at full throttle. A new world with new lights and shadows was being born, told by “La Noia (Boredom)” of Alberto Moravia and “La Dolce Vita” of Federico Fellini. The protagonists of this change were mainly the journalists, that gave a new way of communicating and together with television were the witnesses of the decade that ended with the riots of 1968.

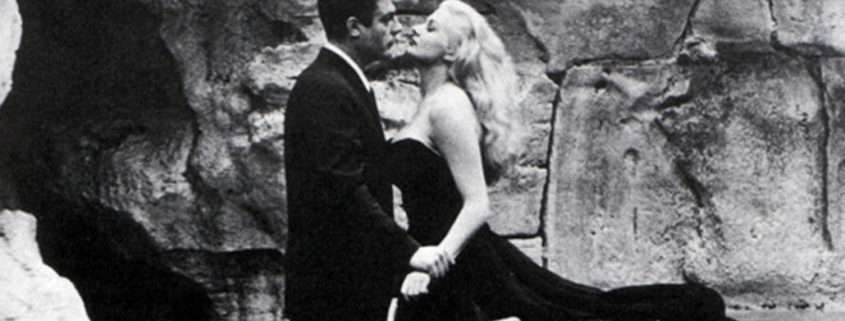

In the film “La Dolce Vita”, society was sarcastically described as an “economic boom” one. Directed in Cinecittà and in the most meaningful spots of Rome, when Anita Ekberg walked into the Trevi Fountain it sparked uproar, said the journalists, and that image became the symbol of an era. Controversy didn’t go amiss and the film was object of a government interrogation caused by the critics moved by the Vatican newspaper “L’Osservatore Romano”, but it eventually escaped censorship. The “dolce vita” became a lifestyle: bars, restaurants and nightlife venues of Via Veneto, gathering spot of intellectuals since the 1920s, started welcoming international stars from cinema and became the stage of their arguments, excesses, flirts and scandals. A detailed description of those events, of which lots of photographers, paparazzis and journalists are witnesses, can be found in newspapers of the time.